Regional differences in performance persist, as do within-state disparities

11x

greater pediatric asthma hospital admissions rate in New York than in Vermont

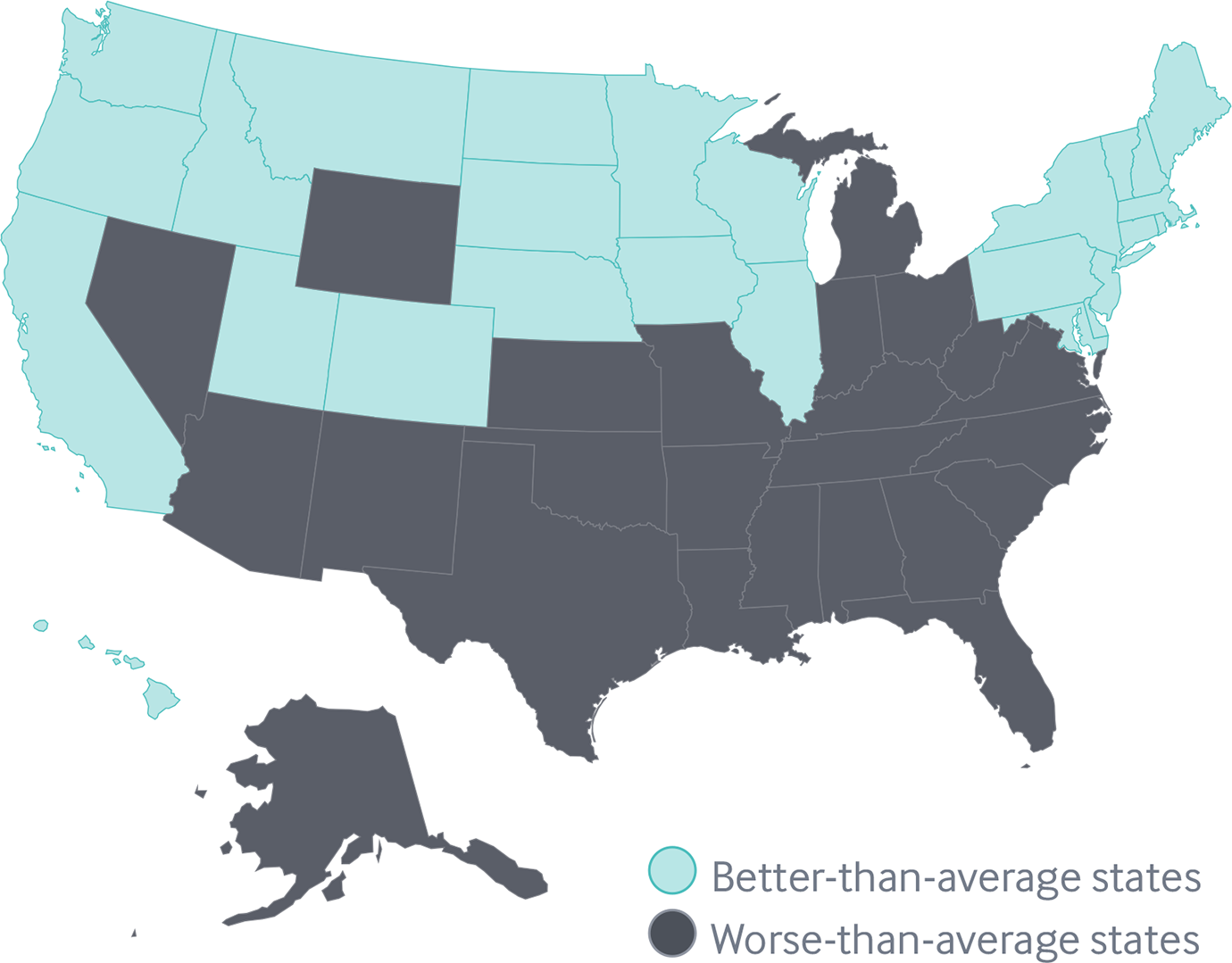

Geographic disparities persist

As previous Commonwealth Fund scorecards have documented, the highest-ranked state generally performs two to three times better overall than the lowest-ranked state.

It’s a stark reminder that where you live can affect both your ability to access high-quality health care and your prospects for a healthy life. Differences between states are most pronounced for hospital admission rates among children with asthma: Vermont had 11 times fewer admissions per 100,000 children than New York did (22 vs. 243).

America’s health care divide

Share

The magnitude of health care disparities within states varies widely when comparing low- and high-income residents

In Alabama, for example, low-income adults are nearly seven times more likely than high-income residents to report skipping needed care because of the cost (33% vs. 5%).

In Pennsylvania, the disparity is much narrower (17% vs. 9%). This pattern of disparities in access to care is mirrored in uninsured rates, which reflect differences in state policies such as Medicaid eligibility.7 Income-related disparities are evident across all the Scorecard’s dimensions of health system performance.

Income-related disparities in health care access differ across states

Note: Uninsured (ages 19–64): U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 One-Year American Community Surveys. Public Use Micro Sample (ACS PUMS); Cost barriers (age 18 and older): 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).

Data: 2011, 2013, and 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).

Share

What Can Be Done?

Socioeconomic disadvantages are a major contributor to disparities in health care and health outcomes across the country.8

In general, people of color are disproportionately more likely than whites to have lower incomes and to be at risk for health care disparities.9 Measuring disparities in health care can help to raise awareness of the need for action, but this is only a first step toward achieving equal opportunity for health.10

What Are States Doing?

Many states are promoting health equity by expanding Medicaid eligibility, engaging in multisector partnerships, increasing health care workforce diversity, promoting standards for culturally appropriate services, and addressing the social determinants of health.11

Oregon’s Medicaid Coordinated Care Organizations, for example, demonstrate how state policy can help narrow disparities in access to care by improving how health services are delivered to patients.12